Imperial Chukkas

Raymond K. Ndokwo

7/18/20255 min read

IMPERIAL CHUKKAS

The British Army Officers Polo Team in 1890s India and the Rise of Martial Elegance

n the age of empire, when the sun famously refused to set upon the British dominions, there arose a breed of officer whose pursuits transcended the theatre of war. Clad in starched whites, mounted on thoroughbred chargers, and wielding mallets with martial precision, these men turned the open fields of colonial India into a new kind of battleground, one defined not by artillery and attrition, but by chivalry, poise, and the gentleman’s creed.

It was in 1890s India, the glittering jewel of Queen Victoria’s empire, that polo—the ancient sport of kings—met its modern muse: the British Army Officer. In these officers’ hands, polo evolved from a regional past time into an international symbol of aristocratic sport and imperial elegance and in doing so, it helped redefine what it meant to be a gentleman in uniform.

I

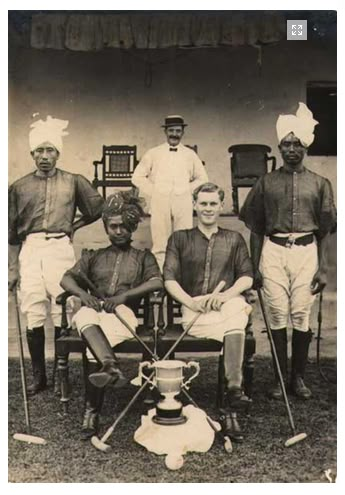

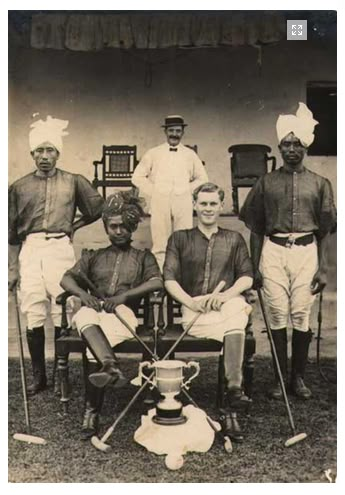

Polo Trophy Maharaja Churachand Of Manipur and Engineer Blackie of the Royal Electricity Department after winning a polo tournament.

India, at the close of the 19th century, was not just a colony. It was the theatre of British aspiration, an exotic crucible in which the values of the English ruling class were tested, refined, and paraded. From Delhi to Calcutta, from Simla’s hill stations to the palm-fringed provinces of Madras, British officers stationed across the subcontinent found themselves not only enforcing imperial order but also preserving a certain standard of civilised distinction. Here, amidst the dust and sun, polo offered the ideal outlet—a sport that was physically demanding yet deeply ceremonial, fast-paced yet laced with decorum. It married action with aesthetics, brutality with grace. To play it well was not merely to be athletic, but to possess that ineffable combination of daring, discipline, and dash that defines the truly debonair.

The Indian climate, with its wide open spaces and historic connection to equestrian sport, provided the perfect grounds. More than just recreation, polo in India became a stage for military camaraderie, officer rivalry, and colonial theatre where bravery and breeding could be displayed in equal measure. Among the most formidable teams of the era were those drawn from the elite British cavalry regiments: the 9th (Queen’s Royal) Lancers, the 17th Lancers, and of course, the famed Bengal Lancers. These were not your average sportsmen, they were soldiers first, toughened by campaigns in the North-West Frontier and Afghanistan, trained to command in battle, yet on the polo field, they exuded a kind of refined aggression, where their tactical instincts were matched only by their horsemanship. Each regiment had its own colours, traditions, and rivalries, but all shared a common creed: to play not just to win, but with honour. Officers who made the polo team were not merely good riders—they were ambassadors of their regiment’s prowess and prestige. A single chukka could determine an officer’s social standing, and many a young lieutenant earned his spurs in the eyes of both command and society through a bold ride or a deft flick of the mallet. Indeed, it was not uncommon for regiments to select officers for service in India based on their polo skills. To be good at the game was to be more than merely athletic, it was to be cultured, cool under pressure, and above all, stylish.

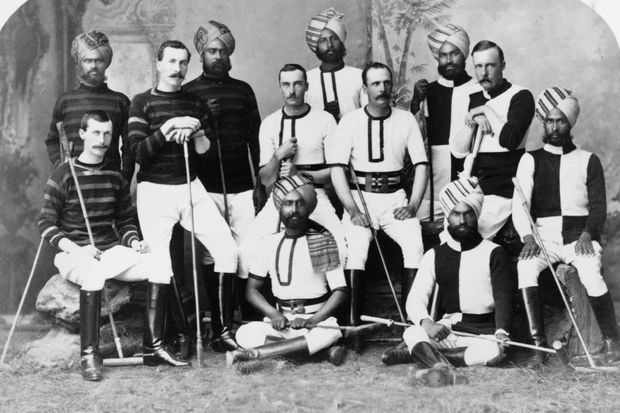

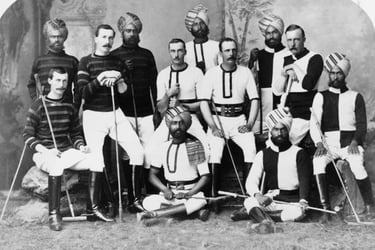

A group of Indian and British officers in distinct polo gear

For the modern gentleman, dress is never an afterthought, it is the foreword to one’s character. So too for the British officers of colonial India. On the field, their appearance was nothing short of ritualistic. Blazers in regimental colours, crisp white breeches, gleaming boots polished to perfection, pith helmets or cavalry caps worn with rakish tilt. Every detail bespoke a sartorial exactitude that elevated the sport into spectacle. And make no mistake, the style wasn’t incidental. In the blistering heat of an Indian afternoon, where dust kicked up in clouds and the sun beat down like a spotlight, the polo ground became a kind of open-air catwalk for martial masculinity. Officers knew they were being watched, not just by fellow soldiers, but by maharajas, diplomats, and society’s upper crust. Their turnout, posture, and comportment told a story: here was a man who could command both horse and conversation, who was as capable with a sabre as he was with a cigar.

Polo, under British stewardship, became more than a sport, it became an instrument of imperial diplomacy. Indian royalty, particularly the Rajput and Sikh princes, had long traditions of mounted warfare and hunting. The introduction of polo as a common ground between British officers and Indian nobility led to a remarkable cross-pollination of prestige. Maharajas such as Bhupinder Singh of Patiala and the Nawab of Bhopal soon became polo patrons and players themselves, commissioning private teams, importing ponies, and erecting splendid polo grounds on palace estates. In this shared arena, colonial hierarchy gave way, momentarily, to a more level playing field, where ability, not ancestry, won the day. Yet even in these exchanges, the British officer remained the sport’s most visible ambassador, setting the codes of dress, conduct, and competitiveness that still define the modern game. In many ways, it was through polo that the British achieved their most subtle form of conquest: the spread of their values under the guise of sport.

The significance of the British Army Officers' Polo Team in 1890s India does not end with history books or fading sepia photographs. It lives on in the very spirit of polo as we know it today. The game’s international expansion from the fields of Rajasthan to the lawns of Hurlingham and the pastures of the Argentine pampas owes much to these pioneering officers who fused military rigour with aristocratic flair. Their model of the sporting gentleman, the soldier who could fight by day and host by night, who could risk life in battle and wager honour on horseback, became a global archetype and it continues to inform the modern debonair ideal: composed, courageous, and immaculately turned out, even in the heat of competition. In many ways, the 1890s British officer on the polo ground was the prototype for the gentleman-athlete, the kind celebrated not just for physical prowess but for composure, charisma, and command. Whether striding into the clubroom or cantering toward goal, he embodied that rare and enviable synthesis of virility and refinement—the very heart of the Ray Boulé ethos.

To understand the deeper elegance of the British officer in India is to understand polo not as mere sport, but as a crucible of character. It was a theatre where empire, masculinity, and style intersected in dramatic gallops and refined gestures. The players were not just soldiers; they were icons of a distinctly Anglo-imperial ideal, where bravery wore a blazer and elegance rode to war. Even now, the image endures: a mallet raised, a stallion in full stride, a figure cut against the blazing Indian sun. It is the silhouette of a legacy—one that gallops, boldly and stylishly, into the annals of gentlemanly legend.

Ray Boule

CELEBRATING THE ESSENCE OF THE DEBONAIR

© 2025. All rights reserved.

By signing up to our newsletter you agree to our Terms and Conditions