THE TWEED GUIDE

Discovering the Debonair: Article 3

FASHIONLIFESTYLE

Raymond K. Ndokwo

11/25/20256 min read

TWEED GUIDE

Editor’s Note

ew fabrics embody British heritage as completely as tweed. From the windswept moors of Scotland to the oak-panelled halls of Oxbridge, tweed has served both the practical and the poetic, shielding its wearers from the elements while signalling a quiet refinement. Once the preserve of the landed gentry, it now finds itself on the shoulders of discerning gentlemen worldwide. This guide revisits the origins, varieties, and modern interpretations of tweed, reminding us why it remains an essential element of the gentleman’s wardrobe.

History & Heritage

Tweed began life as a robust, homespun cloth in Scotland and Ireland, designed to withstand the chill and damp of the northern climate. Woven by hand using undyed wool and simple looms, early tweeds were dense, rugged, and muted in colour. Farmers and labourers relied on them as practical working garments, their earthy tones blending seamlessly into the rugged landscape. One of tweed’s earliest functions was as a natural form of camouflage. Its flecked, mottled surface, created by twisting different coloured fibres together, allowed hunters to merge with the moors and glens. This practical quality would later evolve into the distinctive estate tweeds of the 19th century. The etymology is a tale of accident and geography. Some believe the fabric took its name from the River Tweed, flowing through the Scottish Borders. Others attribute it to a London clerk in 1826 misreading “tweel” (Scots for “twill”) as “tweed” on an order form. Whichever story you prefer, the name stuck and a sartorial legacy began.

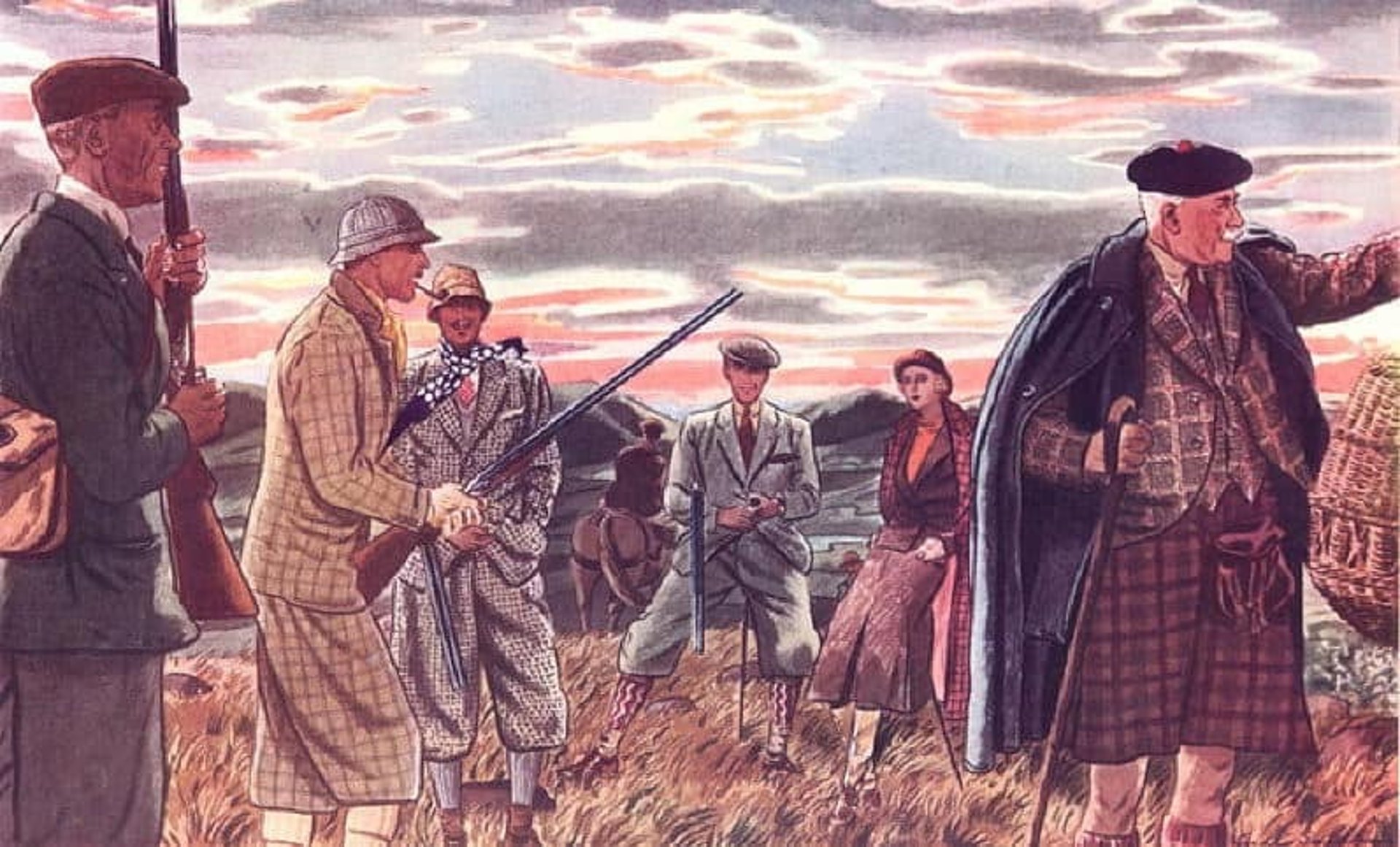

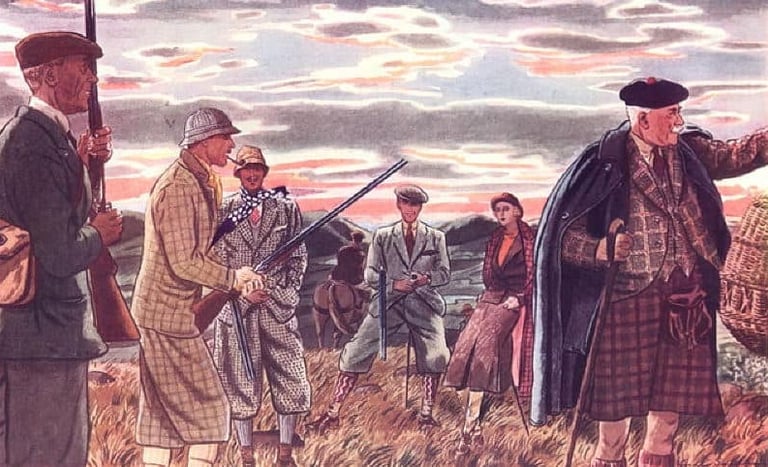

Scottish farmers near Galashiels, c. 1920. Early adopters of the rugged cloth that would become synonymous with British country life.

The Sporting Fabric of Gentlemen

In the 19th century, tweed became the uniform of British aristocrats retreating to their Scottish estates for sport. Prince Albert, husband to Queen Victoria, famously commissioned Balmoral Tweed, a pattern echoing the granite and heather of Aberdeenshire. This marked the dawn of estate tweeds: unique patterns created to identify a specific estate and its occupants.

“Small but pretty… All seemed to breathe freedom and peace, and to make one forget the world and its sad turmoils.”

— Queen Victoria on Balmoral Castle

While Clan Tartans expressed familial identity, Estate Tweeds identified place and community. Workers and guests alike wore the estate’s pattern, fostering a sense of belonging. Over time, the nobility experimented with colours to create distinctive tweeds that blended into their surroundings yet announced their heritage. As the Victorian middle classes sought to emulate the gentry, they adopted tweed for cycling, motoring, golfing, and other leisure pursuits. In an age before synthetic fabrics, tweed was the performance cloth, breathable, insulating, and resilient.

Tweed and the Hunt

Tweed Types and Regional Varieties

Tweed is far from a monolith. Its character shifts dramatically depending on the wool, the weave, and the landscape from which it emerges. These distinctions give the cloth its extraordinary range, allowing it to move effortlessly from rugged countryside use to refined city tailoring. Among the traditional categories that have shaped classic menswear, the first is defined by the very source of the wool. Cheviot tweed, coarse, firm, and naturally lustrous, brings a muscular elegance suitable for both field pursuits and structured suits. Shetland tweed, by contrast, is soft, slightly shaggy, and delightfully informal, reflecting the windswept islands that produced it.

Geography has long played a decisive role in the identity of tweed. Donegal tweed from Ireland is instantly recognisable for its rustic charm and colourful neps, which lend the cloth a lively, speckled surface. Saxony tweed, woven from fine Merino wool, is softer and more urbane, making it a favourite for elegant sports coats and lighter suits. Then there is Harris Tweed, perhaps the most storied of them all. Hand-woven in the Outer Hebrides and safeguarded by the Orb trademark established in 1909, Harris Tweed carries a loose twill weave, a rugged hand, and an undeniable aura of authenticity and prestige.

Tweed may also be classified by function, a reminder of its origins in outdoor life. Gamekeeper’s tweed, weighing upwards of 700 grams, is built for harsh weather, offering insulation and durability. Sporting tweeds, many developed as estate-specific blends, were crafted to provide subtle camouflage during hunting and stalking. Thornproof tweed, made from tightly twisted yarns, resists tearing and withstands brambles with surprising ease; it is famously self-mending, often recovering its surface with nothing more than a brisk rub of the thumb.

Through these variations, tweed became standard attire for English gentlemen during their country pursuits, eventually evolving into the versatile garment cloth we recognise today.

Patterns and Weaves

The true charm of tweed is often revealed in its patterns. While simple twills form its foundation, the cloth comes alive through the classic motifs that have defined traditional tailoring. Herringbone, with its alternating diagonal lines arranged in a subtle V, delivers an understated sophistication. Overcheck adds a secondary layer of interest, placing a check pattern atop twill or herringbone for visual depth and distinction. Barleycorn offers a coarser appearance, its texture reminiscent of small barley grains.

More assertive still are the geometric rhythms of houndstooth and dogtooth, patterns once valued for their natural camouflage in the field. Tweed also embraces the full range of checks, tartans, and plaids, from quiet estate checks to bold, expressive tartans. Whether subtle or striking, these patterns celebrate tweed’s enduring ability to express individuality while remaining deeply rooted in tradition.

Tweed in Society

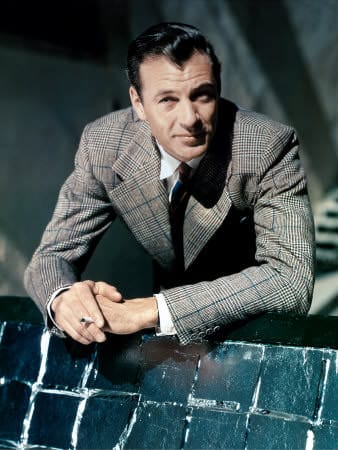

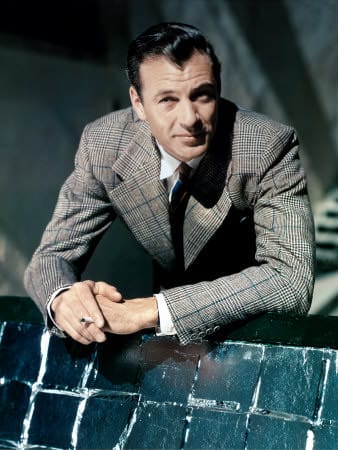

From London clubs to Highland shoots, tweed has long served as a social signifier. In Edwardian and interwar Britain, it delineated the weekend wardrobe from the weekday suit. “No brown in town” may have once ruled, but today tweed has found renewed favour in both urban and rural settings. In cinema, icons like Gary Cooper and Humphrey Bogart gave tweed a rakish glamour, while at Pitti Uomo, contemporary dandies reinterpret it with modern cuts and vibrant accessories. Its ability to oscillate between tradition and modernity is part of its enduring charm.

Gary Cooper in a windowpane tweed jacket

The enduring appeal of tweed lies in its ability to bridge heritage and modernity with effortless grace. A single-breasted tweed sport coat remains one of the most versatile garments in a gentleman’s wardrobe, pairing handsomely with flannel trousers, cavalry twill, or even raw denim for a sharpened contemporary silhouette. In outerwear, heavier weaves come into their own: an Ulster or Guards coat cut from dense tweed offers structure, presence, and a reassuring sense of permanence.

For the man inclined toward full tailoring, a three-piece Donegal or Saxony suit brings rustic elegance into the city without appearing costume-like. Here, restraint is key. The richness of the cloth rewards understated accessories; a silk foulard or knitted tie introduces texture without competing for attention. A tweed waistcoat, whether worn with a full suit or as a separate, provides depth to an ensemble while maintaining an air of quiet distinction.

Choosing accessories in tweed requires a measured hand. A flat cap, a duffel bag, or even a gun case in a matching or sympathetic cloth can add old-world charm, provided such pieces are used sparingly. The aim is not to clad oneself head to toe in tradition, but to evoke heritage with discernment.

Tweed is at its best when complemented by tones and textures that flatter its natural earthiness. Shirts in cream, ecru, or soft pastels warm the complexion and soften the overall look far more effectively than stark white. For trousers, flannel, corduroy, moleskin, and sturdy chinos maintain the textural conversation, ensuring balance from top to bottom. Neckwear should follow suit: wool, cashmere, or madder silk ties offer the ideal tactile interplay. As for footwear, brown brogues, derbies, and dress boots feel instinctively right; black oxfords, being too formal, rarely harmonise with the cloth’s rugged refinement.

Wearing Tweed Today

A Saxony tweed suit paired with a white shirt, silk cravat and a Bordeaux wine-red waistcoat

Choosing the Right Weight

The Enduring Appeal

Understanding tweed begins with its weight. Lighter options in the 300 to 400g range are the most versatile, serving well for casual suits and for wear across variable climates. At 500g and above, tweed becomes excellent coat cloth, robust, warm, and enduring. Beyond 700g, one enters Gamekeeper’s territory, where the fabric is designed for the coldest and harshest outdoor pursuits.

Heavier tweeds, like fine leather shoes, reward patience. They require a period of breaking in, gradually shaping themselves to the wearer’s form. In time, they develop a suppleness and comfort that marks them not only as garments of quality, but as faithful companions in a gentleman’s wardrobe.

“Got my tweed pressed / Got my best vest / All I need now is the girl.”

— Frank Sinatra

Tweed’s continued presence in modern wardrobes is no accident. It represents continuity, a bridge between practical heritage and contemporary elegance. Whether donned for a winter walk in the countryside or a leisurely lunch in town, tweed asserts quiet confidence without ostentation. For the gentleman who values heritage, craftsmanship, and individuality, few fabrics offer such richness. Tweed is not merely a cloth; it is a statement of taste, of tradition, and of timeless style.

F

Ray Boule

CELEBRATING THE ESSENCE OF THE DEBONAIR

© 2025. All rights reserved.

By signing up to our newsletter you agree to our Terms and Conditions