THE WHITE DINNER JACKET

Discovering The Debonair, Article 3

Raymond K. Ndokwo

3 min read

The White Tuxedo: A Study in Quiet Daring

Sean Connery wearing a white single-breasted, peak lapelled dinner jacket. Accessorised by a red-rose boutonnière

In the realm of formalwear, black tie is both a standard and a stage. A ritual of refinement, it demands a certain uniformity—sleek black dinner jackets, satin lapels, well-polished shoes, and that unmistakable sense of occasion. But amid this sea of sartorial symmetry, there exists a garment that speaks not in volume, but in quiet authority: the white tuxedo. It is the choice of the man who understands the rules, yet chooses to interpret them, not for vanity, not for applause, but for the subtle satisfaction of standing alone. At Ray Boulé, we revere this gesture, not as fashion theatre, but as a study in confidence, control, and cultivated nonchalance.

The white tuxedo—technically, a white dinner jacket was born of function. In warmer climates and during tropical evenings, traditional black wool proved stifling. The solution? A lighter, cooler alternative, most often rendered in ivory or cream, and worn with the same components of classic evening dress: black trousers, white shirt, black bow tie. It found its place on verandas in the Bahamas, under the moonlit terraces of Tangier, and at lavish summer galas from Cannes to California. But beyond climate, the white tuxedo carries cultural weight. It speaks of a golden age of masculine elegance, evoking images of Humphrey Bogart in Casablanca, sipping bitters in a Moroccan gin joint, or Sean Connery in Goldfinger, standing statuesque in a Monte Carlo casino. It is a silhouette soaked in cinematic romance, one that whispers rather than shouts—and is all the more powerful for it.

A gentleman in an ivory shawl-lapelled dinner jacket assesorised by a red rose lapel pin and a tobacco pipe

To wear it well is to honour its heritage. The jacket must be ivory or cream, never paper white. A stark white jacket under artificial lighting can appear harsh, even sterile. Cream, on the other hand, flatters most skin tones and glows under candlelight. A shawl collar is ideal, though a well-cut peak lapel can also hold court. Satin or grosgrain facings are essential—nothing should be matte or pedestrian.

Pair the jacket with black evening trousers (always), a proper dress shirt with pleats or a piqué bib, and a hand-tied black silk bow tie. Shoes should be either black patent leather oxfords or opera pumps—no loafers, no experiments. A pocket square in white linen, neatly folded or puffed, completes the look. And perhaps a single boutonnière for the romantic soul.

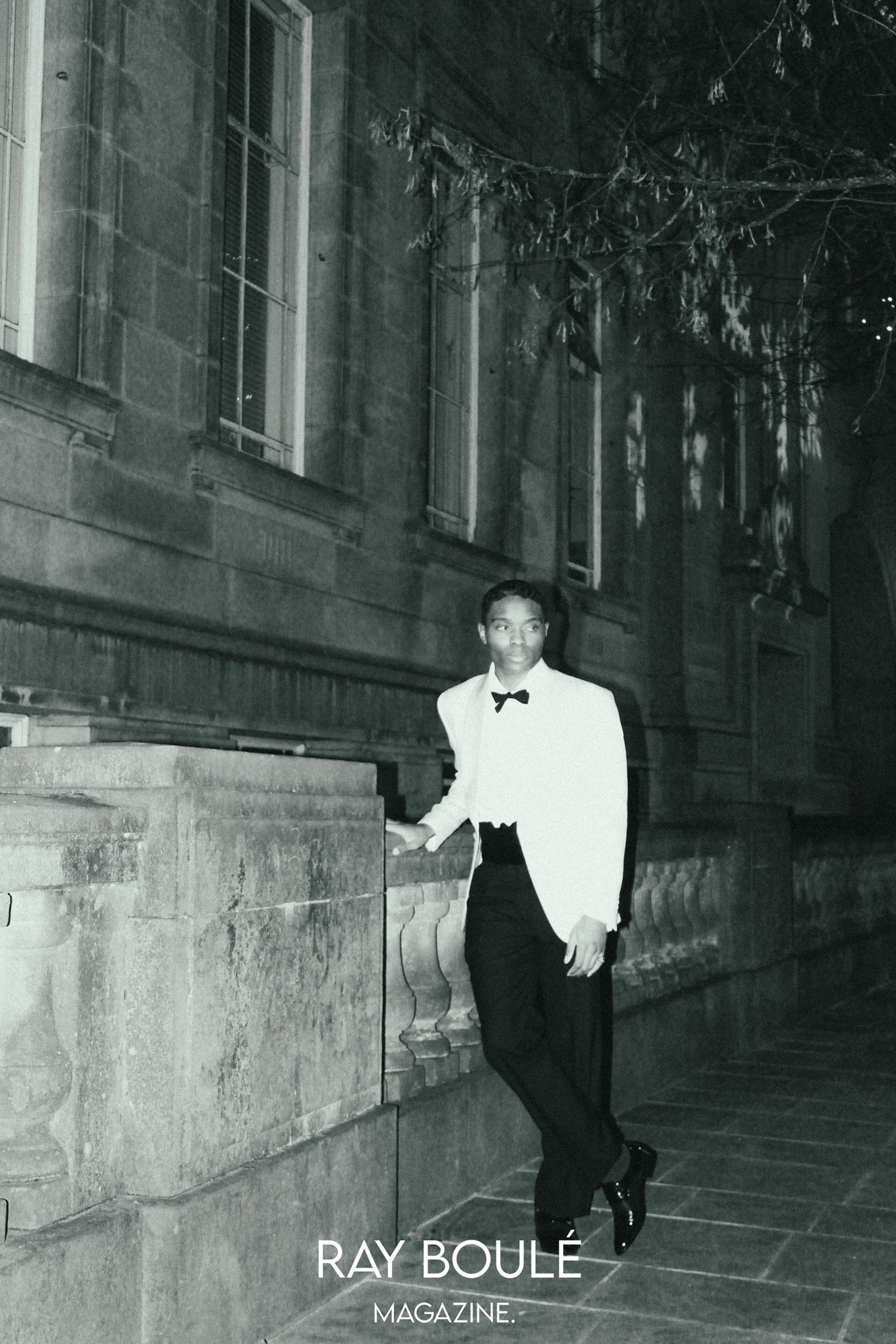

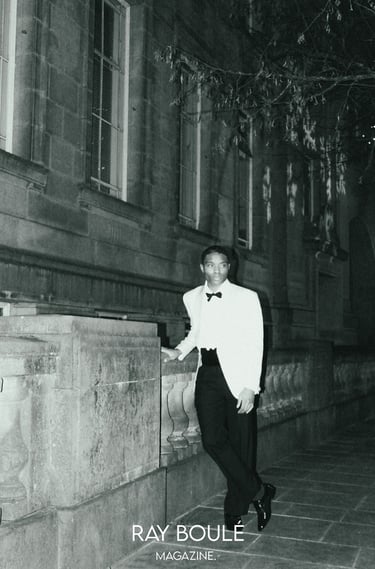

Raymond Ndokwo in a cream dinner jacket, black tie trousers, and patent leather shoes.

The man who wears a white tuxedo does not seek to upstage. He moves differently. He smiles less, but more meaningfully. He knows that elegance is not about decoration, it is about distinction. He enters a room, and though he says little, eyes find him, not out of shock, but out of admiration. At Ray Boulé, we believe that the white tuxedo is more than an alternative; it is a litmus test of taste. Worn with care, it elevates the ordinary black-tie evening into something unforgettable. And while others may dress to blend in, the man in white dresses to be remembered.

After all, true style is not about fitting in. It’s about rising above.

Ray Boule

CELEBRATING THE ESSENCE OF THE DEBONAIR

© 2025. All rights reserved.

By signing up to our newsletter you agree to our Terms and Conditions